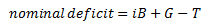

Official measures of the government budget deficit are constructed as follows:

Where:

i = nominal interest rate,

B = outstanding government debt,

G = government expenditure

T = tax revenue (net of transfer payments)

Problems

1) Correction for inflation

This measure does not account for the effect of inflation – a positive rate of inflation decreases the real value of government debt even if the nominal deficit is zero.

If  the nominal deficit will increase by

the nominal deficit will increase by  each year, as will the nominal debt, even if the budget is balanced, but the real level of debt is unchanged

each year, as will the nominal debt, even if the budget is balanced, but the real level of debt is unchanged

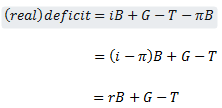

The inflation-adjusted (or real) budget deficit is the official (or nominal) measure minus the effect of inflation on existing debt:

where r = the real interest rate.

2) Accounting for government assets

Most measures of budget deficits only account for changes in government liabilities, not changes in its assets

Some economists argue that the budget deficit should be defined as the change in government debt minus the change in government assets e.g. if a government sold one of its assets the revenue raised would then not reduce the budget deficit since the value of its assets would have fallen equivalently

However, capital budgeting it is difficult to implement since it involves deciding what government spending constitutes expenditure on capital and what does not (e.g. value of a motorway)

3) Missing government liabilities

The standard measures of budget deficits and government debt ignore many liabilities of the government

A) future pension benefits for government workers (equal to about 50% of US debt)

B) future social security payments (estimated to be 300% of existing US debt)

C) contingent liabilities – when the government acts as an implicit or explicit guarantor

4) Adjustments for cyclical economic activity

The magnitude of actual government budget deficits is to a large extent dependent on the state of the economy.

During recessions incomes decline and tax revenues fall whilst unemployment increases and transfer payments rise – leading to a worsening of public sector finances.

During booms the opposite applies and it is easier for the government budget to reach a surplus.

In order to clarify whether a change in the actual budget deficit is due to movements in fiscal policy or economic activity, the business cycle effect is netted out.

A cyclically-adjusted (or structural or full-employment) budget deficit can be calculated by estimating what the government would be spending if the economy was at its natural rate of output

Comparisons of this measure over time reflect changes in the fiscal stance of the government.

The difference between the actual deficit and the cyclically-adjusted deficit is known as the cyclical deficit. For the UK the cyclically-adjusted budget surplus in 1999-2000 was very close to the official measure (1.8%)