Can hearts and minds be bought? A metaphorical question posed to ask whether government spending can aid counterinsurgency. In their paper, Berman et al. seek to answer this basic question using current literature, recent data and a model of counterinsurgency.

They chose Iraq for their research because it is presently significant, there is a large amount of data and most importantly, because it is characterised by insurgency and not by ‘conventional warfare’. It is this characteristic, argued by Berman et al. that will be seen more often in future conflicts that is so crucial to understand. Another important facet to note is that current ‘US Army counterinsurgency doctrine’ is not based on any social scientific theory; thereby making the need to understand insurgency more vital to aid spending.

By using current data, Berman et al. find on the whole that the correlation between reconstruction spending and violence across Iraqi districts is generally positive. At first glance this may seem somewhat shocking. An important question is why this money is being spent when it appears to be doing nothing to aid counterinsurgency. Tarnoff (2008) estimates the U.S. government spent at least $29billion from March 2003 to December 2007 on reconstruction spending. This may have been a waste of money in some people view. However by breaking down the figures and exploring where spending has had positive effects, Berman et al. prove that you cannot ‘judge this book by the cover’. Berman et al. model insurgency as a tri-interaction between rebels, government and civilians, based upon current literature and military doctrine. Put simply, the rebels want political change, the government wants to minimize violence and civilians want to maximise their utility. This basic relation (along with certain assumptions) allows for an in-depth model which, coupled with empirical evidence and testing, brings us to a clearer picture of how government funds should be spent.

Throughout, the paper focuses on funds spent through smaller scale projects, mainly the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP). This is justified as there are problems associated with graft on larger scale projects and because CERP is specifically designed to meet the needs of the local community, whilst at the same time aiding counterinsurgency.

Berman et al. give a brief outline of prevailing and current literature concerning theories of counterinsurgency. They highlight how the change in warfare over time has led to an increased relevance of non-combatants who can have superior information to Coalition and allied forces. Non-combatants are seen as active and rational decision makers. This has the implication that they can be persuaded to change their allegiance (either from rebel to government or vice versa). From the literature they come to the conclusion that the interaction of the three groups in question (rebels, government and the community) is best understood by accounting for the preferences and incentives of all three.

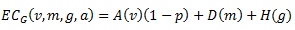

It is argued by Berman et al. that acquiring information from non-combatants is highly valuable and can prevent attacks by rebel groups. They re-enforce this with a famous real life example: ‘the Anbar awakening’ which took place in 2006. A triumph of the Iraq ‘War on Terror’, the ‘Anbar awakening’ was where a change in tactics from the Coalition and Allied Forces meant greater information sharing from the local communities, which led to a huge reduction in violence. To formalise this they create a model based on the Iraqi situation where inevitably, the success or failure of counterinsurgency depends on the community’s willingness to share information. The model builds on an existing model of criminal street gangs created by Akerlof and Yellen 1994, which has its basis from game theory. Each player has actions they can take and the game is played in a sequential order. At stage 1, the rebels favour rebel control, simply because that is what the community is predisposed to. Next (stage2), the government chooses a level of public services and simultaneously, the rebels choose a level of violence. In stage 3, the community then decides how much information to share with the government having observed the previous goings on in the ‘game’. Once they have decided, the uncertainty of control regarding the territory (a) will be resolved (in stage 4) (where 0<a<1, 1 = total government control and 0 = total rebel control). To create their model, Berman et al. first construct a utility function for all three players. The community’s utility is given by:

This assumes that in the case of rebel control, the community does not benefit from government services. This is clearly a strong assumption (buildings can’t easily be withdrawn once given away) which is relaxed more so to simplify the model rather than anything else. It is explored however in the appendix in which they conclude that allowing for non-conditionality in government services only slightly weakens the overall outcome. Rational non-combatants is also assumed which was explained earlier.

The Rebels utility function is as follows:

This assumes that rebels use violence to impose a cost to the Government.

Finally, the government’s utility is given by:

It is assumed the government is not a social welfare Maximiser. Berman et al. shrug this off as a normative criticism and insist that it is necessary to focus on a government with the first priority of suppressing violence. Another critical assumption is that people can be persuaded to engage and share information at a reasonable cost. Without this, there would be no counterinsurgency efforts in terms of information sharing. By using these assumptions and constructed utilities Berman et al. come to a solution for information sharing by the community in stage 3. They also derive three equations that determine the best response functions for violence mitigation, government spending, and violence for the rebel group in stage 2.

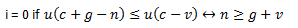

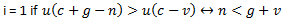

Optimal information sharing by the community in stage 3:

If the utility of community consumption added to government spending minus community norms (where community norms favour rebel control) is greater than the utility of community consumption minus violence, then information sharing will equal to one and the government will control the district. If the opposite is the case, information sharing will be equal to zero and the insurgents will have control.

Best response functions for violence mitigation in stage 2:

Best response function for rebels in stage 2:

As the best response function for rebels is concave, and the best response functions of the government are convex, it ensures the existence of Nash equilibrium where they cross. This Nash shows the level of government services and violence. This will effect what happens in Stage 3 and ultimately, in whose hands the district will lie. These equations can be analysed along with comparative statistics to create testable hypothesis about the situation in Iraq.

The usefulness of a model can be largely affected by the breadth of its application. One district in Iraq could be completely different from another. Consequently an important question for this model is, with varying predispositions toward violence, how should the government apply its services across regions? These varying predispositions will create an omitted variable on a regression of violence on government spending and so it is necessary to see the impact they will have. Berman et al. account for this by looking at comparative statistics in rebel costs and in norms favoring rebel control. They also reference statistics about two other sources of rebel influence, rebel service provision coupled with retaliatory violence and civilian casualties by government. They conclude that the cross sectional correlation of violence on government spending is positive and that none of the above mechanisms are dominant sources of cross sectional variance in Iraqi violence. This positive relationship is seen because of a selection effect. Districts with predictable violence tend to receive high CERP spending and vice versa. However, when holding local characteristics constant, an increase in government spending will reduce violence. This leads us to the three hypotheses outlined by Berman et al. as follows:

H1: A regression of violence on reconstruction spending (of the type that affects the welfare of local communities) will yield a negative coefficient, when controlling for rebel strength and community norms and other local characteristics, which we will estimate in a fixed effects regression.

Essentially they estimate the partial derivate of government spending on violence:

(Where the above holds all local characteristics constant)

H2: The violence-reducing impact of reconstruction spending will be greater when government forces have better knowledge of local community needs and preferences.

H3: Across communities, variables that predict violence should also predict spending on government services.

Using these hypotheses gives a more direct answer to whether government spending has a reducing effect on violence (whilst focussing on CERP spending), and can also give us an understanding of why.

Berman et al give us insight into the data used to reinforce the reliability of their results. They also note the dependent and independent variables, the former being intensity of insurgency activity and the latter being spending on reconstruction projects. They used a variety of sources for their data such as geo-located U.S. government data on violence against Coalition and Iraqi security and World Food Program surveys. Importantly, all sources have been filtered down to remove any bias. Measurement errors have been accounted for and any potential omitted variables have been found to be negligible.

Using the data and hypotheses conjointly allowed Berman et al. to test whether providing public goods have helped to reduce violence. Predictability of violence is a necessary condition for testing the hypotheses since the model links characteristics of regions to levels of violence. By looking at trends in violence by sectarian mix, a clearer picture of the situation within Iraq emerges.

Firstly, violent incidents occur on average around 5-8 times more frequently in Sunni and Mixed areas. Clearly there are two distinct conflicts on the whole, a religious clash in mixed areas and a self-styled nationalistic insurgency in Sunni areas. The figure also shows us a breakdown of violence after 2007 which is when the new counterinsurgency doctrine was put into place. In Sunni areas this breakdown predates the changes the coalition strategy/operational patterns (marked by a line denoted ‘Surge Begins’).

A regression on predictors of violent incidents against Coalition and Iraqi forces shows a key factor in predicting violence is the Sunni vote share. A district that voted entirely Sunni is predicted to have fifteen times the amount of violence than a district that had no Sunni votes. This is reinforced by the fact that the measurement has a bias towards zero as Sunni votes will only represent a handful of Sunni in a district. They also explore the effects of the course of the conflict (time), Shia vote, economic indicators and the strongest predictor of future violence which, unsurprisingly is history of violence against Coalition and Iraqi forces. They conclude that because violence appears to be predictable, government spending should be able to be dispersed appropriately.

Hypothesis 1 can be looked at through a regression on violent incidents on CERP spending. Table IV essentially analyses the derivative:

The first column shows the simple coefficient of incidents on CERP spending which is positive. This was explained in the comparative statistics through the ‘selection effect’. It is predicted violence that attracts the high spending which leads to a positive correlation. Column 2 & 3 take into account predictors of violence discussed earlier and time x ethnicity controls. Here violent incidents decline by roughly two fifths. Column 4 accounts more fully for the possible selection of CERP into predictably violent areas. This results in the coefficient becoming negative which is in line with . Column’s 5 & 6 incorporates lagged changes in violence and district-specific trends to reduce another potential source of selection bias; both however have a negligible effect. To put these figures into context, $10 of CERP spending will cause 15.9 less violent incidents per 100,000 residents over 6 months. Assuming that government spending could eradicate all violence, it would only take on average $37 per capita of CERP spending to do so.

Initially the coefficient is positive. However by conditioning the regression, Berman et al. calculate the negative coefficient predicted. They note that of course there may remain attenuation bias. Because of a lack of data, they had to assume government spending was constant throughout each project whereas in reality this would not have been the case. Spending heavily at one point may have reduced violence largely, whilst at another point in time when spending declines, violence may have increased. The regression however would interpret the data as overall spending vs. overall violence and so may underestimate the spending effect.

Figure VI shows a graphical representation of these results.

The Left panel indicates column 3 of the regression and the center shows column 4. The right panel shows column 4 for 2007 through 2008 and reflects the increased violence reducing effect of CERP spending after the ‘Surge’. This ‘Surge’ included more correspondence with local political leaders and an increased presence of Coalition and Allied forces. To test the effect of this, Berman et al. ran another regression. They conclude that through 2004-2006, the effect of CERP spending was statistically zero, suggesting it was not violence reducing. However from 2007-2008, the coefficient became strongly negative. This indicates that CERP spending was more effective in reducing violence from 2007 onwards. This is all in agreement with.

Another explanation of this counter to is that the violence reducing effect of CERP spending is a proxy for local counterinsurgency effort which increased in 2007. By excluding locations that hold the majority of force presence, Berman et al. test this theory. Two separate tests prove that the violence reducing effect is more to do with the change in tactics of the ‘Surge’ rather than the increased troop presence.

Something that needs to be re-visited here is the fact that the decline in violence in Sunni dominated areas predate any nationwide changes in Coalition doctrine. This contradicts the fact that the violence reducing effect was mainly driven by the ‘Surge’. However, the changes in violence do coincide with ‘Anbar awakening’, the causation of which can be derived down to a change in community norms (n). This is consistent with; in the ‘Anbar awakening’ the government was able to gain a better understanding of the local community’s needs.

The final hypothesis looks at the correlation of violence and government spending. As violence is predictable and column 1 in table IV implies a positive slope, the data should be consistent with . A final regression on predictors of violence also predicting CERP spending was calculated. The results were largely in favour of the correlation being positive at the district level. CERP spending is aimed at areas which are predictably violent. This reinforces the notion that the government is not a social welfare maximiser.

Hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent on the Iraq War and on rebuilding the state. Insights into the way reconstruction money is best spent could help increase the violence reducing effect of this spending and therefore importantly, help to rebuild and save lives. So, can hearts and minds be bought? While this cannot be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’, the findings are still useful. While perhaps leaving many open questions and much to be desired in the form of research, Berman et al. demonstrate that when used appropriately, spending can influence the ‘war on terror’ in Iraq. Indeed, this research can also be applied elsewhere. Berman et al. take a side stance so as not to criticize what the coalition has previously done, but seek to understand the conditions under which government spending can have its greatest effect.

In the paper Berman et al. created a model of insurgency based on a three-way struggle over information. This allowed for a number of testable predictions about service provision and of violence. These were then tested using data at the level of Iraqi districts. They came to the conclusion that although on a regional basis violence and government spending was positively correlated, when conditioning for community characteristics, the opposite is the case. The data shows that from January 2007 onwards (post ‘Surge’), mean violence per capita fell by around 1.6% per additional $10 spent by CERP. This figure becomes more encouraging when you take into account the claim that the vast majority of reconstruction spending wasn’t violence reducing at all. Also, it would take on average $37 per capita of CERP spending to eradicate all violence, if the violence reducing effect of spending was constant.

The paper tells a part of a much greater story yet to be told. It provides knowledge about a programme where spending can work, but the paper lacks insights into broader issues, such as why the majority of spending was not violence reducing and what are the best conditions for government spending to take place. While the paper makes no claim to answer these issues, it leaves us wanting to ask more and question why further research has not occurred as of yet. The paper also indirectly poses a real question about the morality of the government. In the case of Iraq, the government has the first priority of suppressing violence but is by no means a social welfare maximiser (who might instead focus spending on those who need it most). Whether this stance is equitable is perhaps quite subjective, while suppressing violence will improve the lives of some, it may be taking away from others at the margin. All in all, the paper provides a few important issues to consider. The first is that government reconstruction spending clearly can help to reduce violence. The second is that policy makers need to be careful when evaluating statistics put in front of them (there is a difference between correlation and causation). Finally, more attention needs to be devoted to reconstruction spending which is conceivably in some instances, not having the desired effect.

All equations/graphs/hypotheses taken from ‘Can Hearts and Minds be Bought – The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq’ by Eli Berman, Jacob N. Shapiro and Joseph H. Felter

The original paper can be found here: http://econ.ucsd.edu/~elib/ham.pdf